Colombian migrants in Europe tell their story in a book: this is the hidden side of adapting abroad.

From the story of a woman who survived a kidnapping and became the first Colombian to be an Anglican priest in the United Kingdom (Ana Victoria Bastidas) to that of a singer from Cartagena who fuses Afro-Colombian rhythms with pop and rock, winner of the award for best vocalist at the Latin UK Awards (Angélica López), Poetic Memories of the Colombian Diaspora is a collective testimony of more than a dozen women who have migrated, resisted and rebuilt their lives abroad.

Curated by journalist and photographer María Victoria Cristancho—also the external director (trustee) of the organization Mujer Diáspora— this work brings together poems, stories, and photographs born from encounters in which participants transformed their experiences into artistic and healing expressions.

This is the cover of "Poetic Memories of the Colombian Diaspora." Photo: Diaspora Woman

“Emigrating was a decision born of desperation, a leap into the void for a future that promised what my country denied me,” writes Vicky, as she prefers to be known as Ana Victoria. Language, uprooting, and fear marked her arrival in London.

But in the company of other migrant women, she found refuge in faith and community. Ten years later, some of them say, "I feel stronger than ever," as Amparo Restrepo, a trade union leader who sought refuge in the United Kingdom after surviving exile and persecution, notes.

The book is a fabric of living memories: women who left their children behind, who faced violence and precariousness, but who have built support networks.

The first edition, released in 2019, was also an intimate acknowledgment: upon handing that copy to her father, María Victoria Cristancho realized that her own story was also part of that diaspora. Now, in an interview with EL TIEMPO, she shares the details of the second edition, which is being published on the tenth anniversary of Mujer Diáspora and was launched on Victims' Day. The book seeks to honor the experiences of displaced communities.

María Victoria Cristancho at the book launch on Victims' Day (April 9). Photo: Diaspora Woman

Emigrating had been a decision born of desperation, a leap into the void for a future that promised what my country denied me.

We did this using the active memory methodology, created by Helga Flamtermesky, the founder of Mujer Diáspora. It involves not only collecting testimonies but also bringing them into the present. So, I selected a group of women and asked them to write short biographies. We gave first-person accounts and also selected texts from the meetings.

There are four specific second-generation cases: two girls and two boys, children of Colombian mothers, who narrate how they have negotiated their relationship with migration and with Colombia, many without ever having lived there. It was a work of love. Don't expect to find pure literature; what you will find here is pure love.

As a woman from the diaspora whose story is in the book, what is your story? My father was an oil union member in Colombia. In the late 1970s, he went on strike. It lasted six months. During that time, the company began calling workers back one by one until they broke the strike, but my father and another colleague refused. Then he received a letter warning him that they knew where his family lived... That year, they helped him leave the country. He went to Venezuela, but returned, believing everything was calm, but it wasn't. So we had to leave.

Celebration of Candle Day in London by the Diaspora Women's group. Photo: María Victoria Cristancho

My sister and I, twins, were seven years old. We left happily, but later we realized that trip was an escape. We went from having everything to nothing. Being Colombian in Venezuela was extremely hard. We experienced xenophobia since we were children. I was in Venezuela until 2001, then I went to London for the first time. Now, when people ask me if I'm Colombian or Venezuelan, or when they tell me I don't know anything about my country, it hurts.

How do you understand that Colombian identity now? In my house, we didn't talk about Colombia. I never learned to cook Colombian food, I didn't even know how to identify it. To me, it was just food. My mom made beans with legs... And it wasn't years later, in Colombia, that I learned that it was typical Colombian. The music that played in my house was Pastor López, salsa, December music. But we didn't know it was Colombian. It was simply "the music of the house."

So, that Colombian identity was denied to me. And then I saw that many women in London had gone through the same thing.

Meeting of the Diaspora Women's Collective in London. Photo: María Victoria Cristancho

I'd been working with women for a while. I spent five years in West Africa as a correspondent. In Nigeria, I met a group of Spanish-speaking women—there were about 25 of us—and a group called the Ibero-American Women's Group was formed.

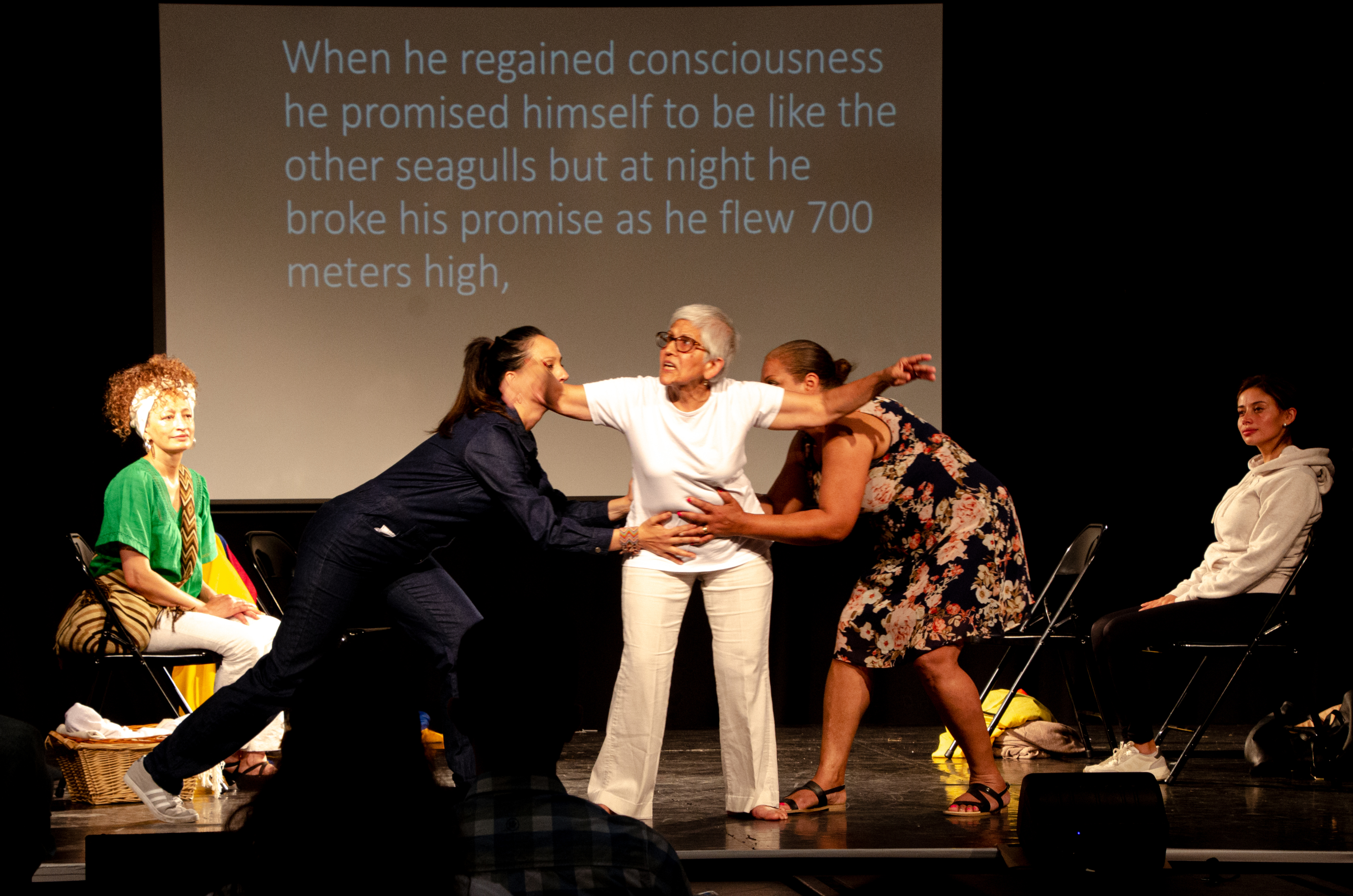

What did you discover with that experience? I found incredible stories. Many of them had left their professions when they migrated. One Mexican girl, for example, had done theater, and we managed to put on a play. My goal was for women to reconnect with who they had been. After a while, I became the documentary filmmaker for Diaspora in London. From there, the idea of putting everything Diaspora does into a book emerged. I've become an advocate for ensuring that these stories aren't lost, that silence doesn't continue to win.

They express their experiences through theater, poetry, and other activities. Photo: María Victoria Cristancho

When it comes to migration, women are the most affected for many reasons. First, in countries like this one (the United Kingdom), the language barrier is immense. Second, they often travel alone, leaving their children behind, with their families... and this creates this dichotomy of abandonment. In other cases, they fail to climb the ladder or significantly improve their socioeconomic situation because they focus solely on working.

What other problems are becoming visible? There are also problems here with women who have married Englishmen... and have experienced violence. There are at least two cases I've followed of Colombian women whose partners beat them. Many come with "partner" visas, so they are subjected to violence because their immigration status depends on their husband.

Have you thought about bringing the book to Colombia? I'll be traveling to Colombia in June and would like to present the book. Everything has been self-organized with the support of organizations like Conciliation Resources, which has supported us in memory and advocacy processes. But we created the book ourselves from the ground up.

Paula Valentina Rodríguez

EL TIEMPO Printed Editorial

eltiempo

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F6a2%2F705%2F215%2F6a2705215f862eb0f0574bcff7d61aa8.jpg&w=1280&q=100)