Psaltery, hurdy-gurdy, rebec and lute: medieval instruments are still alive

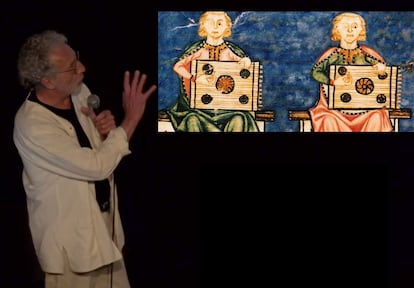

Hands pluck the strings of the psaltery, and its meticulous, vibrant sound emerges from them. Before, other hands cut and sanded the wood that encloses its sound box, shaped the pegs, and extended the rows of strings. The world of medieval music is a world of musicians and luthiers. Both come together to give life to instruments that they have had to learn to build and play by studying codices, or paintings and sculptures in churches. Some of the instruments are replicas of those that have been established by art; others are updated, seeking improvements in sound and technical innovations. Psalteries, hurdy-gurdies, rebecs, and lutes are still alive, and festivals and series dedicated to early music are gradually growing. Such as the Jordi Savall Festival in Tarragona; the Early Music Festival of Valencia; the Early Music Festival of Morella; the Early Music Festival of Granada; the Early Music Festival of Xixón; and the Early Music Festival of the Pyrenees.

“I think the festival circuit is expanding and there's more interest in medieval music . When we started, in the 1980s, there were only a handful. There were many more in Holland, France, and England. So the public's interest is encouraging. Regarding institutions, some support this type of music. In other cases, you hit a wall and there's no way to make people understand that we should look back in time to find our roots,” says Begoña Olavide. She is one of the most prominent Spanish performers of the psaltery and has collaborated with Hespèrion XXI, an international group created by viola da gamba player and musicologist Jordi Savall , a benchmark in the interpretation and recovery of early music.

Olavide earned her advanced degree in flute at the Madrid Conservatory of Music, but her career changed when she met luthier Carlos Paniagua, who became her partner, and she began playing the psaltery. Through their collaboration in their luthier workshop in Mojácar (Almería), as well as in lectures/concerts, they spread the word about the importance of medieval music. “Carlos studied architecture and applies that knowledge to instrument making. He builds them all by hand, even the rosettes, which many now make with lasers. I think that gives them a soul that I certainly feel, and that many other musicians feel. Now there are more people interested in the psaltery and who build and play it, but when we started, no one was doing it. It was an instrument that wasn't preserved in museums; it was completely lost. The Baroque psaltery was preserved, but not the medieval one. That has required years and years of research,” she says. With the psaltery, Olavide plays excerpts from medieval works, such as the Codex Calixtinus, the Cantigas de Amigo by Martín Códax; and the Cantigas de Santa María by Alfonso X the Wise. He also plays music from the oral tradition of al-Andalus .

Although medieval instruments aren't included in the curricula of music conservatories, some do organize workshops for their students to learn to play them. Other courses are promoted by associations and festivals. It's also common to learn directly from an expert musician. This is what happened to David Pérez with the rebec. Although he already came from a family of rebec players from the Polaciones Valley in Cantabria, he didn't play the rebec until the well-known rebec player Pedro Madrid placed one in his hands. "Pedro was in the kitchen of my aunt, Adela Gómez Lombraña, who was a rebec player, as was my uncle Luis, because their parents taught their sons and daughters to play, although it wasn't common for women to play. And Pedro said to me: 'Hey, kid, haven't you ever played?' I said no, and he placed the rebec in front of me. I was probably 13 or 14 years old. Later, I started taking lessons with him in Torrelavega."

It's in this town where Pérez has his workshop, as he's also a luthier. He believes the rebec is an instrument that hasn't been standardized because they're often made in different shapes and materials. "Pedro Madrid built rebecs for the stage. He wanted them to come out of the kitchen, and he started making larger, more spacious instruments. Those of us who came later follow his model somewhat, looking for better tuning. Although I continue to make traditional instruments, because I love the sound of the old rebec with a skin cover and horsetail strings, but for the stage it's more complicated."

The Iberian Hurdy-gurdy Association and the courses it organizes in Casavieja (Ávila) were the gateway to this medieval instrument for Logroño native Jorge Garrido, who until then played the drums and whose musical training came from jazz, which he had studied at the Higher Music Center of the Basque Country (Musikene). Now, with the hurdy-gurdy, he has given concerts as far away as Japan: “There, they are fascinated by everything related to the European Middle Ages and the Camino de Santiago. Here, the audience that attends early music concerts is older. Young people are now becoming interested in folk music, but I think that if more musicians aren't getting into early music, it's due to a lack of awareness. We should give it more visibility and create schools.”

The 11 members of the early music group Aldebarán, founded in the Gamonal neighborhood of Burgos in 1993, play a wide variety of medieval instruments they have acquired through various luthiers. These include the vihuela, fiddle, psaltery, viola da gamba, eight-string viol, rebec, and medieval lute, as well as flutes, chromormons, shawms, and a Renaissance bass drum.

“Most of us studied at the Burgos Conservatory, others in Madrid. We all liked medieval music because we found it very joyful, and we started playing it. At first, we didn't have medieval instruments; we played with prickly pear lutes and bandurrias, guitars, and flutes. Little by little, we started putting on concerts and acquiring medieval instruments. And we also started making medieval costumes,” says Ana María Sánchez, one of the members and a trained guitarist.

Among the musical pieces they perform are some from the Musical Codex of Las Huelgas , from the Burgos monastery of Santa María la Real de las Huelgas , and from the Llibre Vermell , from the Montserrat Abbey. “We have to understand how music was made and how to transmit it. In this sense, the study of the codices is important,” says Gabriel Valenciano, cellist and member of Aldebarán. Sánchez adds that the audience's interest increases when the performance is complemented by explanations about the instruments. “People are delighted because it's something they don't usually see. Although they listen to classical music, it has nothing to do with medieval music. When they come to the concerts, they like to learn about the instruments we have. That helps them immerse themselves in the period.”

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Fe12%2F2e8%2Fb8e%2Fe122e8b8ee944b97d081a0926c511c7f.jpg&w=1280&q=100)