Umberto Eco and the Argentine neighbor of Valencia he 'saved' from the dictatorship

One window of the room overlooks the sea, the other two the urban fabric of El Cabanyal. There, in an apartment in the old fishing district of Valencia, the name of the Italian Umberto Eco is invoked on a hot afternoon in early summer. The semiologist 's affability, erudition, and mastery come up in the conversation, but also lesser-known aspects of the life of the author of The Name of the Rose , such as the letter that helped a young Argentinian woman escape her country's dictatorship or his criticism of "left-wing fascists ."

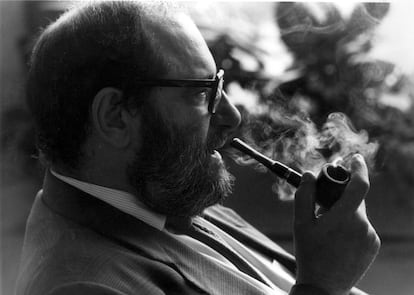

Lucrecia Escudero was that young woman. Today, this Argentine semiotician is 75 years old and commands the attention with her powerful voice. A disciple and close friend of the Italian intellectual and writer, one of the most influential writers of the last third of the 20th century, who died at 84 in February 2016, she is the subject of a new book. Her memories, her life experience, and her relationship with the professore form the backbone of Umberto Eco (declassified). Semiotics of Salvation , by journalist and writer Mayte Aparisi Cabrera. Published by Jot Down, its publication is scheduled for the first quarter of 2026, coinciding with the tenth anniversary of the death of the progressive and anti-fascist intellectual. In his will, Eco expressed his wish that no tribute, symposium, or academic event be held for at least 10 years after his death. Therefore, a flood of new developments is expected.

Umberto Eco (declassified) has the distinction of having been initially conceived in El Cabanyal—without any connection to the professor who taught doctrine from the University of Bologna—with interviews also in Paris, Lucrecia Escudero's two current residences, and of approaching the most human profile of the author and also his personal and political involvement.

“Umberto saved my life, and not just intellectually,” says Escudero, sitting in the El Cabanyal apartment of Cristina Peñamarín, also a semiologist and professor emeritus at the Complutense University of Madrid, whose testimony is also included in the essay. The two have been friends since 1976, when they met at the seminar Eco taught in Bologna. They maintained a personal and academic relationship with him for the rest of their lives and have now bought homes to spend time in the Valencian neighborhood, which was introduced to them by the Paris-based Argentine editor Carlos Schmerkin.

A retired professor who taught at the universities of Lille (France), Córdoba (Argentina), and the Sorbonne Nouvelle-Paris 3 (France), Escudero explains that as a young, rebellious student at the University of Rosario (Argentina), very active and a defender of human rights, she decided to write to Eco to ask if she could study with him. By 1976, he was already an authority in the academic field, but not yet the celebrity he would become years later with the publication of The Name of the Rose in 1980. She had been impressed after analyzing his influential essays Apocalyptics and Integrated and Open Work at the university.

Disappearance of studentsThose were the years of paramilitary crimes in Argentina, of the Triple A, of the subsequent military dictatorship (between 1976 and 1983), and of the left-wing Montonero insurgency. Disappearances were becoming common, especially “of students and workers.” “Many of them were from Philosophy and Literature, like me, some very close to me,” Escudero adds. “So I wrote a letter to Umberto, like someone writing to Santa Claus. I was a good student, but I never expected that by return mail, a few weeks later, a miracle would happen and a letter would arrive on the letterhead of the University of Bologna saying that he had accepted me to work with him in his chair and that he was sending me his dedicated Treatise on General Semiotics as a gift,” she recalls.

With this credential, Escudero applied for the scholarships awarded (and still awarded) by the Italian Institute of Culture, an organization affiliated with the Italian Embassy in Argentina, to study in Argentina. These scholarships are specifically aimed at the country's large population of Italian descent. She won. Fifty years later, the semiologist still gets emotional remembering how she breathed a sigh of relief and burst into applause when the plane took off with numerous students on board, leaving her country behind.

“I experienced the trip as a liberation. It's true that some of the students who also traveled didn't have the problem of militancy and repression or didn't experience it firsthand, but I did, and I wasn't the only one,” Escudero explains. The Argentine recounts in Aparisi Cabrera's book that she kept newspaper clippings in her suitcase containing lists of names of people who had died in military confrontations in Argentina, with only one destination: Amnesty International. “Years later, Umberto admitted to me that when he read my letter, he sensed I was in danger,” she recalls. The writer also conveyed this to Patrizia Magri, who was her right-hand woman.

Escudero recalls that in his first meeting with the intellectual in Bologna, he already showed his naturalness and complicity, inviting him to eat a pizza and confiding his satisfaction, but also a certain fear: "He had just bought a ruined convent in the middle of the mountains, and since he was married to a very strict German woman, Renate Ramge, I didn't know how to tell him."

The conventThe convent played a prominent role in the writing process of The Name of the Rose , a medieval detective novel and compendium of cult references that was very well received by critics, some of whom, however, distanced themselves from it when it became a worldwide popular success, with tens of millions (half a hundred according to some estimates) of copies sold. Last April, Milan's La Scala premiered the operatic version, composed by Francesco Filidei, which will also be performed at the Paris Opera.

All of this is discussed in Aparisi Cabrera's book, which presents the lesser-known and more familiar side of Eco in a research work that rescues the oral memories of some of his main disciples, with special attention to his ties with Argentina.

The book chronicles Escudero's 1990 meeting with an Italian diplomat at the Italian Cultural Institute in Paris. He told her that the institution "was aware that with the scholarships awarded during the years of lead," they were helping to save young Argentines.

In any case, the Italian Institute of Culture in Argentina did not carry out an organized operation, nor did the Ministry of Foreign Affairs have anything to do with it, according to diplomat Enrico Calamai, speaking with EL PAÍS in a telephone conversation from his home in Rome, as reported by Federico Rivas Molina from Buenos Aires.

"It could be that the director of the Institute helped, but as a personal matter, or that Eco wrote to the Foreign Ministry in Rome," notes the 80-year-old diplomat, who was working at the Italian embassy in the Argentine capital at the time. Previously, Calamai had served as vice consul in Santiago in 1973, a position in which he assisted and protected hundreds of Chileans who entered the Italian embassy fleeing Pinochet's coup.

At the Italian Institute in Buenos Aires, "there was a committee composed of Italian and Argentine officials who validated the candidacies." "If the Italian side insisted, the candidacy could be accepted. If it had been a well-known guerrilla, it would have been very difficult. There were also many people who were in danger, who had left the organizations and had not yet been identified," he adds.

Psychoanalyst Cristina Canzio, a friend of Escudero's, met Calamei in Buenos Aires before also receiving a scholarship in Italy. Her sole motivation was to study in Florence with Graziella Magherini, the psychiatrist who coined the term "Stendhal syndrome" or "Florence syndrome" in 1979, which refers to a psychosomatic disorder caused by exposure to works of art. Her home in the Italian city was a stopover and contact point for some Argentines fleeing the dictatorship in those years, she notes by telephone.

Now, Cabanyal is becoming a meeting place for new neighbors. There, Escudero is renovating a ground-floor apartment on one of the streets that preserves the popular architecture (eclectic, modernist, humble) of a neighborhood that went from neglect and the threat of pickaxes to the fashionable. From there, she calls on the teacher and friend who "changed her mind" and made her realize that she "had been a left-wing fascist ." Eco questioned the bloodshed in the struggle of the Montoneros and the revolutionary Peronists of the 1970s, whom she compared to Italy's Red Brigades, which assassinated Aldo Moro, thwarting the possibility of implementing the historic commitment advocated by PCI leader Enrico Berlinguer to seize power in alliance with the Christian Democrats, as recounted in the film "The Great Ambition ," recently released in Spain.

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Fd99%2Fba0%2Fdd7%2Fd99ba0dd7cc423cf51a5052a76bf355f.jpg&w=1280&q=100)