Without TV money, Mughini sells his beloved books. A tale of friendship and money.

A Life in First Edition

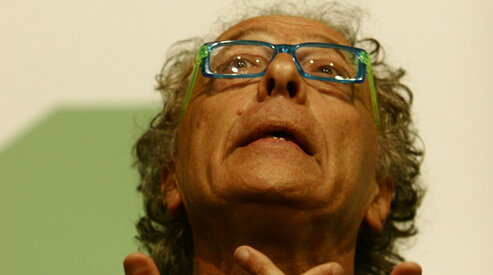

Among the twenty-five thousand beloved and sought-after volumes, the lost friends, the interrupted television, and the money seen as freedom, Giampiero Mughini is putting his own museum up for sale. Interview with "Mughenheim"

He's dismantling the museum on himself. But he's joking about it. Giampiero Mughini needs money— "No one offers me a job anymore. Ever since I got sick, everyone stopped calling me"—and so he'll sell his precious book collection . "The first editions of Pavese, Calvino, Campana, Gadda, Sciascia, Fenoglio, Pirandello, Bassani, Moravia, Bianciardi, Montale, Ungaretti... In life, I've never been able to put anything aside, except my books." The point is precisely this, simple and brutal: they no longer let him work in television, where, for years, he worked well and successfully. And so he's made the decision, which sounds very much like a farewell, to dismantle his house-museum : "My soul is being ripped out of me," he says, while a strange, ironic little crease forms around his closed lips. He's the same Mughini as always, and it's a flash. “...But then again, no one has ever had a complete soul, not even the saints.”

He never counted all his books precisely—among them, many first editions from the twentieth century—but he estimates they number between twenty and twenty-five thousand volumes. And within them, some absolute rarities like the first edition of "Coscienza di Zeno," published in 1923, beige cover, black type, 328 pages, approximately 1,500 copies printed at the author's expense. Then "Ossi di seppia" (Gobetti, 1925, print run: 300 copies), "Gli indifferenti" (Alpes, 1929, 1,300 copies, also self-financed), "Il giorno della civetta" (Einaudi, 1961, I Coralli no. 163). Beloved books, pursued like trophies, collected with jealousy and instinct. One can only begin with a stupid question: have you read all twenty-five thousand volumes? "The ones that allowed me to write some of my own." Now, however, he's selling his most valuable ones to a Milanese bookseller, Pontremoli, with whom he's had a relationship for half a century. A surrender, indeed. "But I won't sell some, I couldn't. The three books by Italo Svevo, which are legendary rarities. The books by Umberto Saba, because I wrote a book about Trieste that I care deeply about, and then Carlo Dossi, who I liked for who he was. I think I resemble him, Carlo Dossi. He was someone who reinvented himself every day. In my opinion, Dossi was one of us in the '60s." What was he like? "He was a man of a thousand interests, unclassifiable, not aligned with one side or another."

It's here that the ironic twist returns to his lips. A man forced to dismantle the museum of himself, yet ready to joke about it, to talk about it with a mix of pride and regret. But Mughini is fine. Or at least that's what he says, with that way of contradicting himself as he speaks. "I've had health problems. But yes, I'm fine now. But if you tell me to go from here to my bathroom, I'll have a bit of trouble," he laughs. "The doctor told me in very clear language that I've reached the point where I have to 'manage' my old age. I hadn't realized, mind you. Because I'm quite old. Eighty-five, to be precise." Pause. "Death? I don't think about it. Because if I think about it, you'll get a big head."

And what's selling books? "It's an indispensable suffering. The sale will be accompanied by a catalog. So at least one book remains mine, and they even sign it. Yes, it's heartbreaking. I do it because it's necessary. The only job I have is the article I write every Tuesday in Il Foglio. With that I follow an intermittent diet, which they say is also good for my health." So I ask Mughini if at least his pension provides him with something. "Of course." And if he's put aside any money. "Pit." Pause. "But he spent with gusto... Yes, you can see that." He extends an arm toward the surrounding rooms, the beautiful house where we're sitting, full of books, paintings, memories.

Television, which for years had brought him popularity and earnings, suddenly came to an end. "It was fun, that season in front of the cameras," he says. Then he shrugs: "They don't call me anymore: never mind, maybe I wouldn't have been able to handle another reality show with mosquitoes. But talk shows, yes, I miss those." And then there's the TV paycheck. "Oh, sure. I did it, TV, partly because it allowed me to live the way I wanted." With a lot of money.

And Mughini isn't shy, never has been, about talking about money. In fact, he considers it an integral part of his personal vocabulary. On money, he's clear: "Not talking about it is hypocrisy. Look, I've never done anything for free, for example." And then he tells of a friend who once called him: "I'd like you to do this," the friend said. And Mughini, with a grass-blade smile, "Sure, I'd love to do it. Tell me what the fee is." "We don't have a fee." Obviously, he avoided the question.

And it's at this point that this man dressed entirely in jeans, shirt included, formulates his rule, which he christens with doctrinaire irony: "Look, I'll tell you now what my system of thought is, my Marxism-Leninism." You're welcome. "First, under no circumstances lay a finger on anyone who thinks differently from you. Second, under no circumstances lay a finger on a woman who doesn't want to. Third, never do a job for free... and if you quote a book, it's because you've read it. This is my Marxism-Leninism."

The point, he insists, is not "enrichment," but the practical evidence that without money, you can do nothing, you can't get anywhere: money as a measure of freedom, choice, work. Not the superfluous, but the necessary. It is the logic—cold and clear—that today leads him to dismantle his library, after a lifetime spent building it.

Any betrayal from TV friends? “Evaporated. But I assure you I've consoled myself very well. They weren't friends.” Has all this happened in the last three years? “In the last two years. To tell you the truth, I was worse a year ago. Now I'm getting better, fortunately.” You have a degenerative disease. “I also do physical therapy.” And so they don't call him. Yet for years everyone has been looking for him, they wanted him everywhere: talk shows, reality shows, “L'Isola dei Famosi,” “Dancing with the Stars,” football arenas, political roundtables. “I really enjoy doing television. They ask you X, you answer Y, and meanwhile there are thousands of people looking you in the eye while you talk.” Pause. The usual grass-blade smile. “Proust doesn't need to be looked at face to face… but I do.”

An intellectual among the fans. Why football? "Because it's popular. If I'd talked about Brasillach on TV, I wouldn't have had that success." An intellectual fan. "Juventus fan." But Juve is now in dire crisis. "Juventus should change its name. It was the team of the Agnellis and the Italians. Today, it's neither one nor the other. Maybe the entire Serie A should change its name." His voice becomes sharp, bitter, but still capable of transforming pain into a parable. "It's a formidable metaphor for Italy. Kids don't play ball in the courtyards anymore; they're on social media with their phones. It's nothing like football."

And so, once the lights are off, the house remains. A four-story 1930s villa in Monteverde Vecchio, which Mughini has transformed into a walled-up autobiography. The "Muggenheim," what remains of a life. We're sitting on the ground floor, in a room entirely lined with shelves: the bookcase encircles all four walls, as if it had traced the very perimeter of his life. This isn't the collection he's selling: the volumes surrounding it remain here, preserving his memory. Those that will leave are only the rarest pieces, the heart of his passion as a collector. Outside, on the facade, a sign declares: "This house is inhabited by Leonardo Sciascia, Andrea Pazienza, and others." Not a whim, but a sign of gratitude. "Because this house, which was a ruin and which I restored, is full of their works. I've always seen the house as a sort of autobiography. And this house is my autobiography: the things I've loved, the books I've loved, the artists I've loved."

His friendship with Sciascia was genuine, the kind that comes through books and trust. "He brought me an article that L'Ora di Palermo had rejected, and I published it in Giovane Critica." When Sciascia died, he was preparing a book on Telesio Interlandi. "Interlandi's son called me and said, 'Why don't you write it?' And so I wrote that book, 'A Via della Mercede c'era un racista'. Who knows how Sciascia would have written it?" A sly look: "I think I wrote it 'fairly well.'" Interlandi had been the editor of the fascist magazine La Difesa della Razza, a name that carried with it all the infamy of the racial laws. An extraordinary book.

With Andrea Pazienza, however, it was a bond of gazes and irony, of elective affinities between two irregulars. Then Norberto Bobbio. "I did I don't know how many interviews with Bobbio, hours and hours. He didn't speak to anyone, he didn't give interviews to anyone. But with me, yes. His intelligence was like a tank: if you had crashed into it, you would have shattered to pieces."

Talking about his library means touching the very foundations of his life. Each book is a fragment of memory, and memory takes him back to the city he left behind, to the roots he fled. Catania, where he was born, and which he abandoned in 1970. “But my city is Rome,” says Mughini. “A city where there's room for everyone. You know, Rome welcomed someone with 6,000 lire in his pocket and gave him something. Only in Rome did I find someone who said to me: 'Listen, write an article for the Astrolabio.' And it was here that I began to be a journalist. With some success, I'd say.” Just being in Rome was like taking up a trade, a profession, or a course of study. Living in that great city meant learning, understanding the world, sniffing the wind. “If I had stayed in Catania, at best, I would have become a middle school French teacher.”

The separation from Sicily was stark. "I felt suffocated in Catania. The atmosphere was... worse than provincial, in the worst sense of the word. At a certain point, the Catania newspaper, La Sicilia, started a war against me because I was a leftist. And so in 1970 I took a train, second class, of course, and with nothing in my pocket I came here." Next to you was Anna, "a girl who held her own. Maybe without her I wouldn't have made it."

My eyes then fall on two black-and-white photographs on the bookshelf: the face of a beautiful young girl, and the stern profile of a man in his fifties. Who are they? "My grandfather and my mother."

“My grandfather was a communist, Sicilian. My father, on the other hand, a Tuscan who moved to Sicily for work, was a staunch fascist. So my mother, the daughter of a communist, married a fascist. Then they separated very young.” An early and scandalous separation for the time. “My mother would have been twenty-five at the most. She spent her life alone. She had a man she was seeing… and one day, when I was 13 or 14, my father took me to the window and said, 'Do you know that your mother is seeing a man?' I replied, 'And she has every right to.'” And here Mughini's face lights up. His eyes darting under his half-closed eyelids. “I consider this answer one of the things I'm most proud of in my life.”

And how did you cope as the child of separated parents in a time when no one else was? “Not well, but what could I do? In Catania I had no choice. I decided very early on: either I leave or I die.”

When was the last time you returned to Catania? “For many years, my mother was there every summer. At a certain point, she expressed a desire to come to Rome, to be with me. But I was working non-stop at the time. I didn't let her come. She died alone in Sicily: one of my greatest regrets.”

It was the exhilaration of a career that suddenly opened up: the discovery that success could come without mediation, without protection, with just your voice and your persistence. Rome gave him the feeling of living a hundred lives in the same day, and he wanted more. And it was in that state—consumed by commitments, the daily rush, the need to never stop—that his mother's request to move to Rome remained unanswered.

The province, however, doesn't deny it, Mughini. "Sicily has given, it has indeed given. As for Catania, there aren't many names, but Vitaliano Brancati alone would be enough to save it, not to mention De Roberto, Verga..."

When he talks about the province and its writers, the conversation inevitably veers into politics. Mughini's polemical spirit reignites. "Do you know what the most empty word in circulation today is? The dry division between fascism and anti-fascism. Certain words have become like Upim warehouses; you can find everything inside, from graters to Persian rugs. Fascism no longer exists; I don't see what anti-fascism could consist of." It's the same kind of thinking that led him, in 1977, to co-author "Piccolo sinistrese illustrato" with Paolo Flores d'Arcais. That book—I tell Mughini—should be reread today, by the left. Perhaps Elly Schlein should read it? "But I don't know if she'd understand. If anyone isn't suited to reading that book, it's Schlein, because she's the living embodiment of left-wing. The very embodiment." That booklet even had a preface by Giorgio Bocca, who, speaking of the left of that time, almost seemed to describe today's pneumatic void. "Sinistrese is generic, demagogic, inconsistent," Bocca said. "It's a smokescreen that never settles, a buzz that never translates into personal, precise, concrete, responsible commitments. We 'carry on,' we 'fight,' we 'help' each other among comrades against the reactionary fascist enemy indicated by the sinistrese where it doesn't exist or where it's just folklore."

And what was Giorgio Bocca like? “Well, Bocca knew how to move. He was considered a leftist, but he wasn't someone imprisoned by the left's patterns.” His preface was a blessing from the left to your book. “Yes, it was a blessing, but one he had done reluctantly.” Why reluctantly? “First of all, I think they paid him little. And I think he was attached to money.” Wasn't he nice? “He was as tough as a clod of wheat from the Langhe. The preface was requested by that excellent publisher, Massimo Pini.” Those were the years in which Mughini's relationship with the left, from which he came, became increasingly tense. The publication of “Compagni addio” (1978) marked a watershed, even a personal one. It was a book that spoke without indulgence of the generation that grew up in revolutionary illusion and ended up amidst extremism and dogma. An indictment that the left didn't forgive him for. “When I came out with 'Compagni Addio,' Carlo Muscetta, my teacher, told my mother he didn't want to see me anymore. Can you believe it? Professor Muscetta…”

And it wasn't just Muscetta. Marginalization and slander were perpetually open traps for the minds least inclined to conformity and obedience: they were waiting for only one small misstep to spring forth like a cleaver. "Nanni Moretti was truly a dear friend of mine. Then, out of the blue, he stopped talking to me. The very last time I saw him, not too long ago, I ran into him nearby and said, 'It's been years, but let's stop this between us. Will you come to dinner at my place?' And he said, 'Yes, I totally agree, I'll see you the day after tomorrow for dinner.' Never saw him again." What is a bad temper? "A bad temper is giving one hundred percent importance to one's own affairs and zero importance to the affairs of others." Politics as religion, violence as language. Is there any connection between the extremism of the 1970s and what's happening in Italian universities today? "No, not similar, in the sense that from that pandemonium emerged none other than the Red Brigades. Now there's no hint of anything resembling the Red Brigades. What's happening in some universities is certainly shocking: first they take away your voice, then they attack you."

I ask him if he's ever thrown a stone. "A stone in May, yes, on the night of the barricades." And have you ever used a crowbar? "No." Then there's the experience of Il Manifesto, which he was also among the founders of, and which closed quickly: "I resigned after three months. They wanted to create a new Communist Party." Pause. "I, on the other hand, thought what was already there was more than enough." A meaningful look from Mughini follows. "I presented a letter of resignation to Luigi Pintor." Did he stop greeting you, too? "Of course. Once in the street he pretended not to see me, and I said to him, 'Luigiiiiii, come on.'"

And today? Would you ever vote for Giorgia Meloni? “Absolutely not. But watching her political developments with sympathy, yes. She's a very clever girl. I met her when she was almost a child, during a public meeting. And already then she made a great impression on me.” But who do you vote for then? “I don't vote anymore. I'm not interested in politics. I think the last time I voted was for Renzi, who was secretary of the Democratic Party. I like Calenda, for Beppe Sala... but like I said: I don't vote. I have zero interest in party politics.” All right, Giampiero: we're done. The interview is over. “And how much do you plan to write?” I don't know, a page, I think. “Hmm. Look, one thing I've learned in my job is that if you write something in sixty words instead of a hundred, it comes out better.” So I provoke him: if you had to reduce your life to a single sentence, what would it be? “On my grave, you could write, 'Here lies a good man.' And for once, no one will be able to contradict me, because I'm no longer here.”

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto