<i>Sinners</i> Celebrates the Rich Tradition of Black Vampire Stories

In Sinners, blood isn’t just life—it represents memory, resistance, grief, and desire. It flows thick and slow through the Delta heat of 1932 Mississippi, where twin brothers Stack and Smoke (both played by Michael B. Jordan) open a juke joint that pulses with rhythm and energy. They think they’re creating a sanctuary, a space to dance, to dream, to forget. But what they find is older than music, older than the land itself: vampires, hidden in plain sight. Their presence makes it clear that some hungers—spiritual, historical, generational—can’t be outrun.

Ryan Coogler’s Sinners is a revelation; a blood-soaked horror epic rooted in Black Southern memory. But more than that, it is part of a long, lush, and often-overlooked tradition of Black vampire storytelling—a genre that has never been simply about monsters, but about being transformed by trauma and finding beauty in the aftermath.

Black vampires have always done something different than their European counterparts. They usually don’t sparkle, and they rarely isolate. They gather and carry ancestral memories. Their horror is communal and rooted in survival rather than just individual consumption. In the hands of Black creators, the vampire archetype becomes more than a predator; it is an archivist of pain, a sensual being forged—but never fully defined—by relentless violence. It symbolizes what it means to exist forever in a world that was never built to see you—and to demand to be seen anyway.

This is why the current resurgence of the Black vampire—on screen and in fiction—feels less like a trend and more like a reclamation.

Take AMC’s Interview with the Vampire reboot, which portrays Louis de Pointe du Lac (played by Jacob Anderson) as a Black Creole man in 1910s New Orleans. That shift didn’t just diversify a well-worn story, but reframed it entirely. Louis wasn’t just struggling with immortality—he was navigating the effects of racism on his quality of life, class, desire, and his place in a world that demanded silence. He became a metaphor not just for the erotic or the eternal, but for conformity, for suppression, and the cost of survival. His transformation wasn’t just physical—it was existential.

Jacob Anderson as Louis De Point Du Lac in Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire.

This speaks directly to one of Sinners’ most haunting undercurrents: assimilation. The vampire’s bite becomes more than a lethal wound—it’s an invitation into a system that promises power, access, and even immortality, but demands a steep toll in return. As Zoé Corrine (@zoxzo2), an artist and film enthusiast, noted in a TikTok analysis, in Coogler’s hands, vampirism reads as an allegory for the price of entry into whiteness: the erasure of culture, the quiet brutality of fitting in, the slow disconnection from community and self. It also reflects how, historically and in the present day, non-Black people of color—and those deemed “close enough” to whiteness—have not only been asked to prove allegiance through anti-Blackness and complicity, but have often done so willingly, whether out of fear, ambition, or the allure of access, trading solidarity for a seat at a table that was never set for them.

“As a history buff, the movie Sinners had my mind reeling with theories. I spent undergrad at Howard University where we not only focused on the Black experience, but world history as well,” Corrine tells ELLE.com. “So after watching the film, I was immediately able to make that connection. Movie experiences that are nuanced like this are the kind I go crazy for.”

Assimilation demands a shedding—of language, of history, of memory—until you belong to something that will never truly belong to you. And at the center of it all is white supremacy’s bottomless appetite—not just to dominate, but to devour, to consume until nothing unfamiliar remains. The vampire in this context doesn’t just feed; it colonizes and tries to rewrite history.

That’s the magic of Black vampires: They show us that transformation can be both a curse and freedom. That becoming something else—something feared, something powerful—sometimes seems like the only way to survive.

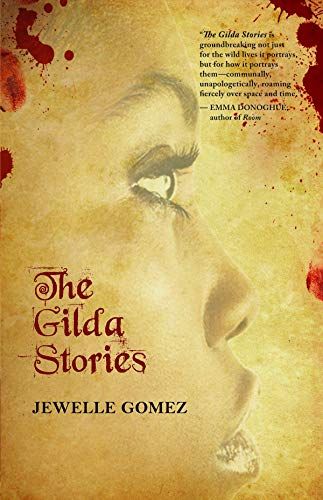

This tradition isn’t new. It stretches back for generations through literature, film, and oral storytelling. In 1972, Blacula exploded onto the screen, fusing Blaxploitation flair with Gothic dread. In Octavia Butler’s controversial 2005 science fiction novel Fledgling, we meet Shori, a genetically altered Black vampire who is 53 years old in an 11-year-old’s body. After surviving a massacre, she must rebuild her identity—piecing together who she is while challenging everything we think we know about family, power, and consent. Jewelle Gomez’s The Gilda Stories follows a Black lesbian vampire from the 1850s into the future—not as a predator, but as a protector—centering communal care, queer chosen family, and survival without bloodshed. These aren’t just stories of violence and death. They’re stories of rebirth, of self-invention, of legacy.

A poster for Blacula

They also allow for play, which is rarely afforded to stories about Black suffering. There’s eroticism here. Glamour. Subversion. The Black vampire doesn’t just survive the system but flips it inside out. They wear velvet and smoke cigars, like Blacula in his signature cape and midnight charm. They seduce with eyes that have seen centuries, heavy with the aftereffects of enduring, like Louis in Interview with the Vampire. They say no to death on someone else’s terms, like Gilda, who chooses care over violence and reshapes what power can look like.

Vampire stories, especially those told by Black creators, offer a kind of temporary relief. They give us permission to be angry, to be extravagant, to be immortal.

They also ask hard questions, like: What does it mean to carry generational trauma in your body? What happens when your pain becomes your power? Who do you become when you’re no longer trying to survive?

“As very human-looking immortal monsters, vampires act as the perfect vehicle for the human experience throughout history,” says Hayley Dennings, the New York Times bestselling author of This Ravenous Fate, a YA novel about an 18-year-old lesbian vampire navigating life at the height of the Harlem Jazz Age. “Black history is horrific on its own without the added presence of supernatural beings, but the immortality of vampires reminds us how the past never really leaves us—and how history and trauma continue to impact us.”

For Dennings, Sinners felt like “a masterclass in storytelling,” she says. “As a writer of Black horror and queer fantasy that explores Black womanhood and sexuality, it was amazing to see so many of those aspects on-screen in such a major film.” Through her reimagining of vampire lore, Dennings resurfaces histories that have long been buried. “History and blood can’t be separated from vampires,” she says, “just as they’re inseparable from the Black American experience.”

In Sinners, the vampire isn’t just a threat—it’s a mirror. Smoke and Stack are forced to reckon not just with the creature’s violence but with their own histories of loss. And this is perhaps the deepest cut of the genre: the way it binds horror to ancestry. It tells us that even the dead aren’t done speaking.

Michael B. Jordan as Smoke and Stack in Sinners.

“There’s a forbidden freedom in these stories,” says Mika Ahlecia, founder of Black Girls Who Write, who’s long had a love for vampire and paranormal tales since childhood. After watching Sinners, Ahlecia took to BookTok to reflect on its impact and share Black vampire reads that carry a similar emotional gravity. “It wasn’t just a vampire film—it was about community. That first act, with people coming together for one night of joy and escape, felt like everything I’ve been building. And then the twist made you think deeper—about history and spirituality. I left the theater wanting to peel back every layer.”

As Sinners ignites conversation and curiosity, a new generation of readers are turning to books that hold this same rich emotional depth. Christina C. Jones’s Blackwood: After Dark vampire series blends romance, mystery, and the supernatural in a Black town where desire and danger coexist. In I Accidentally Hooked Up With a Vampire, Jessica Cage flips a casual fling into a biting, genre-bending ride where queerness isn’t questioned and you’re free to fall in love on your own terms.

These books don’t just diversify the genre. They make it deeper and richer. They turn it into a playground where we can explore identity, grief, intimacy, and imagination. In a world that relentlessly demands proof of Black humanity, these stories—where fantasy and reality collide—don’t just entertain. They awaken a magic rooted in legacy.

elle