The Roman Theatre of Mérida, Spain, was the setting for The Tragedy of Coriolanus

The Roman Theatre of Mérida, Spain, was the setting for The Tragedy of Coriolanus

The production was presented at the International Festival of Classical Dramaturgy

▲ The staging of Shakespeare's play introduced modern elements, including the theme of La Llorona. Photo courtesy of the festival.

Jorge Caballero

Sent

La Jornada Newspaper, Tuesday, July 29, 2025, p. 4

Mérida. William Shakespeare's Coriolanus was presented with a new vision by director Antonio Simón, featuring performances by Roberto Enríquez, Carmen Conesa, Manuel Morón, and Álex Barahonda, among other actors.

The work surprises from the start with the modern elements it integrates, such as the iconic mask from V for Vendetta, a graphic novel created by Alan Moore, and the traditional Mexican song La Llorona, which plays throughout the astonishing work set in Rome at the beginning of the Republic, but which reflects on current situations.

In an interview with La Jornada, playwright Antonio Simón commented: “My first encounter with Coriolano was many years ago, and I always knew I would stage it one day.”

For Simón, this production has been updated over the years and perfectly reflects the interplay between ethics and politics

. He emphasized the timeliness of the piece and its marvelous composition, emotion, and lyricism

, like any work by the English playwright. Added to this is the fact that it is ideal for a large audience, as required by the Mérida International Classical Theatre Festival

.

According to the Barcelona playwright, "the character of Coriolanus contributed to the social and political uncertainty experienced at the time, because the people were hungry. It was the beginning of the Roman Republic; the motto 'Rome, Senate, and People' had not yet been established, but there was an aristocracy that governed for its own interests, with enormous classism."

Simón explained that in this context, the presence of "a representative between the interests of the aristocracy and those of the people was urgently needed, in order to found a solid Republic." In other words, the characters realize at that moment that changes are needed. This is where the character of Coriolanus appears, who clings to the old laws and feels classism and enormous contempt for the people; thus, a confrontation between these social classes erupts. The paradox of the play is that the characters who contribute to founding the Republic are very corrupt.

There are no heroes in this work. It unfolds within a very perverse plot, although in the end, the Republic is saved and ends with the personal tragedy of the protagonist, who ultimately succumbs to his own personal inconsistency. Furthermore, he is a being dominated by his mother.

Regarding the modern elements introduced into the staging, such as the costumes, the masks, and the theme of La Llorona, the director mentioned: it's a participatory play, in which the audience identifies with the actors: at times it's the people of Rome and, at others, the Senate or the army. I wanted to build a very direct relationship with the audience in a vast space, like the stage of the Roman Theatre in Mérida; it was achieved very well, because the audience participates a lot, very actively. In Shakespeare's time, the audience was like that, very participatory; the playwright's idea is based on the Elizabethan theater of his time. From there, one of the lines of the show was articulated: one in which the audience experiences what they see. That's why the play is contemporary, without, of course, being realistic

.

For his part, the director of the event, Jesús Cimarro, considered that "Coriolano reaches the midpoint of the program to tell this emotionally charged and intense political story."

Simón concluded: the audience will have to analyze the work and engage with certain textures and how ethics and politics intertwine. It's an emotional production, with tragedy, lyricism, and violence, along with some sexual overtones of the era

.

Alejandro Loredo shares La jarana de arco, a sound project that took him 12 years to complete.

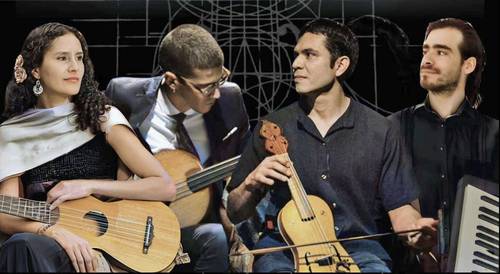

▲ Raquel Palacios, Vico Díaz, Alejandro Loredo, and Sebastián Espinosa performed at Jazzatlán Capital. Photo courtesy of the artists.

Merry Macmasters

La Jornada Newspaper, Tuesday, July 29, 2025, p. 5

Musician Alejandro Loredo presented his project , La Jarana de Arco, in a concert held at Jazza-tlán Capital, where he had guests such as Raquel Palacios Vega, soprano and jarana player, bassist Vico Díaz on the leona, and pianist Sebastián Espinosa. Loredo performed the soprano jarana de arco and the requinto. Playing the jarana with a bow is his own concept.

During the two-hour performance, they heard traditional sounds such as El cascabel, El pájaro cú , and El aguanieves, and experimented with Baroque musical sounds, such as folías and some Bach pieces, the latter performed by Díaz and Espinosa, which come from other genres such as classical music, jazz, and rock. "Although with the freedom to give them the license of accentuation and musical prosody that we have in accordance with the heritage we have each created

, but with the license of the music we all play, which is the traditional music of the Sotavento

," Loredo points out.

The bowed jarana began 12 years ago; it aims to promote the sound of the instrument that gives it its name. It seeks to recover the bowed string sounds of the son jarocho

, explains the performer. These instruments were lost over time for various reasons; only remnants remain in the Tuxtlas region: a small rebec known as the Tuxtleco violin, due to its shape

.

According to Loredo, there was a generational gap in which these instruments stopped being made. However, in recent years, the jarana has been revived. From then on, I realized there was an unexplored field in both luthier and music: the sounds of bowed strings. This is because the so-called Tuxtlas violins are generally very small instruments with some construction problems. I say problems with great respect, especially considering their insertion into more global music, a situation that son jarocho is currently experiencing

.

Beyond its traditional rural context, son jarocho has expanded significantly over the past 30 years. Its connection with other genres has led to the development of the luthier's instruments so that they can match the tuning, volume, and playability of more universal instruments, Loredo notes.

For a long time, he points out, peasant music was very marginal, which meant that instruments were also made in precarious conditions. This, in other areas, can be a problem, for example, with tuning

.

Over the course of 12 years, Loredo has crafted instruments in various ranges; however, for the past 18 months , I have managed to consolidate the instrumentation of a tenor bass, a contralto, and a soprano, and to arrange both traditional and new music for them

, which has allowed him to give solo concerts.

Create community

A few months ago, as part of the promotion of the bowed jarana, Loredo invited traditional and contemporary musicians to create together. One of the main drivers of this process, aside from creativity and having one's own instrument, made with endemic woods and with the perspective of contemporary son, is to create a community. It's an instrument that aims to embrace all the possibilities within son jarocho

.

The bowed jarana "descends from the Iberian vihuela, which, in turn, influenced other cultures. Around the 16th century, they formed a family of instruments: the vihuela de mano, the vihuela de plectro, and the vihuela de arco. Much music was made with them on the Iberian Peninsula, both popular and culterano, because they had sufficient elements: different ranges and interpretive qualities.

“Here I understood that the jarana, as a descendant of the vihuela, also had plectrum and hand instruments; so the question was: why don't we have bowed jaranas?

While researching, I realized that at different times in history there are records that in the son jarocho in particular there have been bowed instruments of various shapes and sizes, so it seemed pertinent to me to create bowed jaranas.

Pablo Ortiz Monasterio reveals the memory of Mexico City

Merry Macmasters

La Jornada Newspaper, Tuesday, July 29, 2025, p. 5

Everything has a memory, says photographer Pablo Ortiz Monasterio: "Walls hear, floors feel, and the sky sees

." They tried to make ancient Tenochtitlan disappear; however, it re-emerges in the hands of a graffiti artist who makes a painting that reminds me of a pre-Hispanic figure

, the artist says on the occasion of Tenochtitlan, a 40-image exhibition at the Museum and Archive of Photography, which adjoins the base of the Templo Mayor, where the tzompantli was.

In that context, the exhibition is an offering to our ancestors, to the people who built that empire that abruptly collapsed following the emergence of Europe; I'm not evaluating whether it was a good thing. They tried to erase it, but no, everything has a memory

.

A new exhibition on the subject, also by Ortiz Monasterio but with different images, is on display at the Galería Abierta de las Rejas in Chapultepec. The starting point for both exhibitions is the forthcoming book "Tenochtitlán" (Editorial RM), with text by Álvaro Enrigue.

On Reforma Norte, Ortiz Monasterio recalls, there's a property before reaching La Lagunilla that's almost submerged, where there's always water. Even in May, the driest month, you can see an aquatic plant that used to be a feature of the lake. Of course, there's a lot of trash, graffiti, and people living there; however, the memory of the lakeside city persists

.

Another glimpse

comes in gastronomy, at a street stall selling esquites accompanied by chayotes, not the smooth kind, but the one with thorns, which are peeled and peppered. It's a heritage eaten in the center of the country. I've never seen it anywhere else

, the photographer notes.

Twenty-nine years ago, he published the book The Last City, with text by José Emilio Pacheco; it was a multi-award-winning title. Cities, however, change, they age. The Tenochtitlan project was born at the end of the pandemic, a time when we were all desperate; so, I decided I would systematically go to downtown Mexico City, but by bicycle, to ride around with my camera

.

That's when Barbara E. Mundy's Death of Tenochtitlan: The Life of Mexico (2018) fell

into her lap. “When I read it, I began to understand things and learn a lot, because Mundy delineates the boundaries in the 16th century, as far as the Mexica settlement reached. It was no longer the original islet, because they had been living there for about 200 years. I said: 'that's the key.' That's the territory I'm going to explore. At that moment, I wasn't thinking about the 700 years since the founding of Mexico-Tenochtitlan.

Today, on that site that was once an island surrounded by water, the pavement continues endlessly; so, there's a kind of visual island. If you walk carelessly, you don't notice it; but if you pay attention, you discover elements that emerge like water.

Exploring the territory is a conceptual project. In Mundy's book, I realize that the only curved street in the Historic Center is República del Perú Street, because there used to be a canal there. They later drained it and made a street. There's the memory of the hidden aquatic city

. For the purpose of the photo, Ortiz Monasterio went on a Sunday morning, a day when there are no street vendors, so that the curve could be seen from a distance.

The exhibition is divided into three sections: Pre-Hispanic, Colonial, and Modern Bodies. Throughout the project, there are many figures

: idols

, Christs, and saints, followed by mannequins, which are often very sexy

. The figures are the common thread.

My project is designed to intertwine images: so that one connects with the other. In the exhibition, I sometimes place two in a single frame, and the viewer sees them as a single piece. For example, there's one of a young man, or a young woman, we don't know, because he's wearing a face mask with the image of a sexy woman, with painted lips, whose counterpart is a stone statue of a nun who lacks a head; therefore, it has no mouth. Linking two images generates things that weren't present in either of them and creates other possibilities for interpretation.

Ortiz Monasterio highlights the ways of looking at the project: In a book, you can only see two open pages at a time, while in an exhibition, the images are seen up close and from a distance, in different parts of the room. The experience on the street is different. Some people walk through the exhibition at the Chapultepec Gates from beginning to end, from the Museum of Modern Art to the National Auditorium. Most people, however, view it from their cars or on public transportation; therefore, these characteristics must be taken into account and adjusted

.

Tenochtitlan will remain at the Photography Archive Museum (República de Guatemala 34, Historic Center) until August 31.

jornada