An essayist must be able to answer for himself completely. Jesi failed to do so.

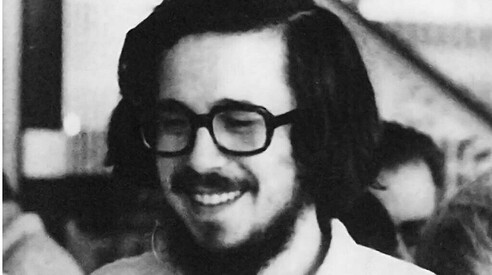

PHOTO Google Creative Commons

reply to Sofri on the intellectual absent from our anthology

The breadth and depth of the historian's expertise are unquestionable. With his early death, we have lost one of the most beloved Italian intellectuals of the second half of the twentieth century; but not, we believe, one of the most solid writers.

On the same topic:

Thanks to Sofri for his repeated attention to our anthology of Italian essayists. But it's an unsatisfying attention, as was to be expected. In all anthologies, there's always some author who, according to some readers, should have been included, but instead is excluded. In truth, it must be said that we chose the path of acceptance rather than selectivity precisely to avoid, as much as possible, the book being discussed primarily to avoid claiming that such and such an author was unjustly absent: this is, in fact, the quickest way to denigrate an anthology, making it more suspect than credible. Massimo Onofri, in Avvenire, lamented the absence of Salvatore Satta, and we don't believe there's any need to argue: it was our mistake or (worse) an unforgivable oversight. Now Sofri is complaining at length , writing an entire article deploring the non-anthologization of Furio Jesi . In this case, however, the exclusion was deliberate and sufficiently justified, at least from our point of view.

The breadth and depth of Jesi's expertise are undeniable. But we, the editors, have agreed on two flaws from the outset. His best-known and most appreciated book is the one on Right-Wing Culture: the flaw here, in our opinion, is that Jesi, with all his baggage of more or less esoteric knowledge (Egyptology, mythology, and Germanic studies), has constructed a sinisterly nocturnal, witchy, and diabolical portrait of right-wing culture, completely neglecting that if, in matters of culture, we want to discuss political categories like left and right, then we must be talking about politics, not the unconscious, perversions, and thanatologies. The politically strongest right, because it is more realistic, is not the Nazi one; rather, it is the liberal-conservative, cynical, and paternalistic one, for which the state can be authoritarian but not dictatorial, and acts to defend the free market at all costs—that is, at the cost of neglecting the safety and well-being of exploited and defenseless majorities.

Jesi's book fails to see this, and so his Cultura di destra (Culture of the Right) lacks the right that matters most, more realistic and less attracted to sinister mythologies. Jesi's second and more pertinent flaw is the literary poverty of his essays. But this flaw is not entirely distinguishable from the first: because in the essay, as in every form of literature, the style is not ornamental but cognitive. Jesi's fundamental theme is the role played by myth in art (Rilke, Pavese, Mann) and politics (its exploitation, especially modern). It is a theme that immediately lends itself to essayistic use, if it is true that the essayist is the writer who can grasp the conceptual analogies between characters belonging to different spheres of culture and reality. At the same time, however, in handling myth, one is tempted to reduce the analogies to a game of equivalences where "everything is in everything." Jesi knows this. He knows it because he is extraordinarily erudite, and because he is extraordinarily sensitive. It's no coincidence that he often finds himself encircling, with his interpretation, those symbols that "rest in themselves," that is, those that are now suspended between a state of fungibility and one of annihilation. And his encirclement prevents them from falling into the darkness of hermeneutic indistinction.

And yet—here's the problem—since Letteratura e Mito, Jesi has been pursuing precisely that path: he refuses to draw the less favorable conclusions, but he doesn't change it. Thus he becomes sophistical, especially when he tries to defend certain authors (Rilke, Pound) from those who, not without reason, accuse them of arbitrarily aestheticizing the symbols of Western tradition. Thus, again, when he himself is about to slip into the same trap, he draws back, wriggles, but precisely for this reason he becomes elusive and cumbersome. If he isn't so in the passage cited by Sofri, it's because there Jesi chooses to give in to the overinterpretative, allegorical, and mythologizing temptation of a Hoffmann story, preemptively reducing it to a "parlor game," that is, carefully placing it in ironic quotation marks. The stylistic hesitation, the imperfect interlocking of his pages, reveal that he cannot otherwise "discharge to earth" the enormous cloud of analogies he evokes. Which is to say that he isn't entirely sure of the connections between his scholarly interests and other areas of life, that he can't fully answer for himself: an essential condition for an essayist. Would he have achieved this, had he lived a little longer? It's difficult to say. Certainly, with his early death, we have lost one of the most beloved Italian intellectuals of the second half of the twentieth century; but not, we believe, one of the most solid writers (and thinkers). In our anthology, however, some of the recurring motifs in Jesi's work are represented by authors such as Carlo Michelstaedter, Nicola Chiaromonte, and Ernesto De Martino.

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto